WTO moratorium on E-Transmissions and OECD Pillars for digital economy

Moratorium on Cross Border E-Transmissions

If one imports a book into India, one will pay applicable customs duty (currently 10% basic customs duty, and all applicable cess/welfare charges). However, if one downloads the same book over Amazon Kindle, one gets it duty free. Kindle books are almost always cheaper than their paper counterparts and the zero import duty is one of the factors keeping it that way, other factors being savings on printing/paper, transportation etc. This is an example of how the moratorium on international cross border taxation on Electronic Transmissions (ET), adopted by WTO in 1998 affect the prices.

|

| Share of Digitalised Products in Global Imports - as represented in UNCTAD study |

Also, there is the question of direct taxation, in terms of corporate taxes or taxes on profits from the earnings made in India for companies who are highly digitalised in terms of delivery/users/markets (Amazon cloud services, Facebook, Google), and where it is not easy to actually segregate the amount of profits that arise out of operations in any particular tax jurisdiction/country. I am not aware how Amazon India accounts for the kindle sales in India, and the subsequent profits or lack thereof and whether they are adjusted against subsidised goods sales and so on while filing the annual tax statement with the Indian government. The case becomes complicated when you look at free ebooks offered under 'Kindle Unlimited' scheme. It is not easy to establish the nexus between the operations and profits arising in any one country when the model is highly digitalised. Therefore, in a digitalised world, where companies are operating in a highly digital model, both indirect and direct taxation becomes a vexing issue. While WTO bothers more about indirect taxation such as customs duties, OECD bothers about direct taxation such as corporate tax on profits and issues related to Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.

For those who understand how digital transmission works, the issue of tarrification of electronic transmission (WTO issue) and the issue of taxing profits of digital multinational organisations (OECD issue) are two sides of the same coin. You cannot actually isolate one without stepping into the other part. But for now let's deal with them separately and frame the policy questions in these areas from India's point of view.

The indirect taxation issue

The matter of indirect taxation basically pertains to customs duties that don't exist currently on electronic transmissions due to a WTO moratorium agreed by members during 1998 and which continues with extensions till date. There is a now a debate about whether the moratorium needs to be ended and countries be allowed a framework to impose customs duties on electronic transmissions. At stake is the potential revenue implications which vary in calculation, with a range that varies from 280 million USD to 8.2 Billion USD per year, and which even at the higher end appears too small to actually matter. However, few countries including India wish the moratorium to end this year after it lapses leaving the members free to impose duties on cross border data and electronic transmissions.

There is no doubt that the consumers would be at the receiving end of any such tax/duty. But more importantly we need to analyse as to whether it would work in favour or against India. There is a successful IT and ITeS sector in India that depends on electronic transmissions. If we decide to impose tariffs on certain types of electronic transmissions, we may expect reciprocal taxes from partner countries on our types of electronic transmissions, and which might damage our competitiveness in IT/ITeS. The cost/benefit analysis therefore should go beyond mere 'revenue loss' mindset and should include the reciprocation effects. Software lobbies therefore oppose the move and present cogent arguments. Also, it's not easy to determine the methodology of taxation due to origin issues. The netflix videos that one watches on the mobile/computer/TV receives packets of data. These packets arrive from nearest possible servers which need not be located in one country. A typical HD movie might get millions of packets which may be served from eight different countries. To isolate the amount of taxation for each arrival would be methodologically complex. The complexity increases with characterisation of the data being transmitted. Some data can be called services, some can be IP and some transmissions such as designs might involve a royalty. Even if a simple methodology is developed to characterise the transmission and tax them, there are chances that firms may use routing protocols to minimise border crossings and taxes.

India's unique placement

However, despite the above challenges, India's case is unique. India is is one of the biggest importers of digital products using E-Transmissions as can be seen below.

|

| WITS database - Net exports of physical digitizable products |

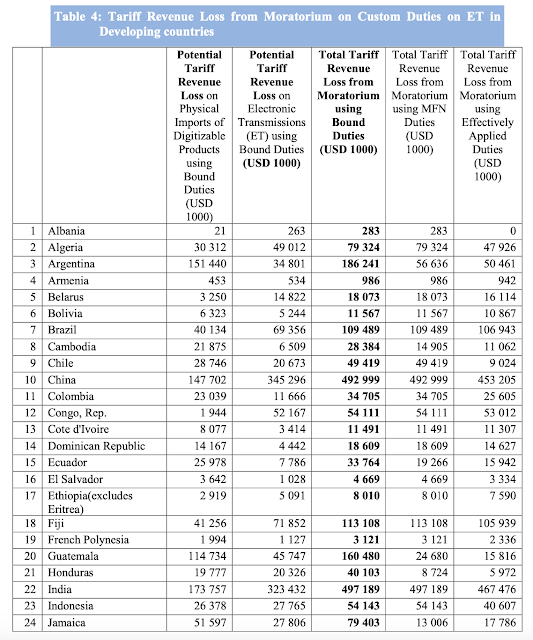

The UNCTAD study has arrived at a potential revenue gain of around half a billion US dollars for India if India decides to opt out of the moratorium. The number projected as India's gain is greater than sum total of gains that might accrue to all developed countries put together if the WTO moratorium ends. Also, this number is unmatched by any other developing country and explains India's position towards ending the moratorium.

|

| Potential revenue gain by ending WTO moratorium |

However, the above numbers are controversial and blamed for presenting only one side of the coin. In a paper, Hosuk-Lee and Badri Narayan argue that the potential gain through revenue collection through border taxation on these activities would get offset by the losses that would accrue to the GDP due to this taxation. They summarise the losses and gains as follows:

|

| GDP and Tax losses upon imposition of tariffs |

In short, they argue that a tariff gain of half a billion USD would lead to a tax loss of 2 Billion USD due to decreased GDP, decreased investment, welfare loss and loss in employment. These figures are for a scenario that the authors create where other countries reciprocate upon ending of moratorium. The authors also argue that there might be concomitant employment loss of around 12,70,000 jobs upon reciprocation. They feed in the indirect taxation into direct taxation issues of corporate profits and end up painting a bleak picture if moratorium ends.

(On a side note, the paper feels too pessimistic to read and serves as an effective counter to the UNCTAD study.)

India needs to seriously do an independent analysis of the whole issue before pitching one way or the other. Relying solely on UNCTAD study might not be enough to take a call.

The policy question on indirect taxation

Therefore the correct question for policymakers in the area of indirect taxation should be: "Is it really worth to trade away the competitiveness of IT sector, employment, tax losses, and consumer welfare for a potential tariff revenue in terms of customs duty that appears so meagre to start with, and which is difficult to implement?"

The question is loaded in a way that it self-answers. But if you look at it carefully, the answer is: "It depends."

The direct taxation issue and the OECD's Unified Approach/GloBE under Pillar One/Two

Coming to the question of direct taxation, OECD, while making the final report in the matter of 'Addressing the tax challenges of digital economy' during 2015 stated that "because the digital economy is increasingly becoming the economy itself, it would not be feasible to ring-fence the digital economy from the rest of the economy for tax purposes."

From that conservative view in 2015, OECD evolved its way through the interim report on the matter in 2018 and finally a policy note in early 2019 which in turn evolved into full discussions leading to a public consultation document titled "Secretariat proposal for a 'unified approach' under Pillar One" during Oct-Nov 2019. Under this document, the matter of taxing digital multinationals has been pried open with the idea of taxing them based on location of revenue generating users over the earlier principle of place of physical presence of business. This will disrupt the existing tax position and settled way of working for Amazons and Facebooks.

Chiefly, the issues being dealt by OECD under Pillar One are:

- the allocation of taxing rights between jurisdictions;

- fundamental features of the international tax system, such as the traditional notions of permanent establishment and the applicability of the arm’s length principle;

- the future of multilateral tax co-operation;

- the prevention of aggressive unilateral measures;

- the intense political pressure to tax highly digitalised multinationals.

The discussion hovers around:

- reallocation of taxing rights in favour of users/market jurisdiction over the existing principal location of business for highly digitised businesses

- The nexus rule that would be independent of physical presence in users/market jurisdiction

- going beyond arms length principle currently in practice for related entities across borders

The matter is work in progress.

However, what's noteworthy is that the three corner positions on Pillar One are clear. The first corner is of US which wants taxation based on market intangibles, the second corner belongs to France and EU which wants taxation based on user participation, and the third corner belongs to India which wants the new nexus principle wherein level of physical presence is ignored in favour of amount of business generated in a tax jurisdiction. The negotiations shall evolve over time and the three corners should reach a consensus point wherein a final unified approach evolves and agreed by all.

The Pillar Two pertains to Global Anti Base Erosion Proposal (twisted to fit the short-form: GloBE) wherein rules are being discussed to avoid multinationals in digital economy from shifting bases and profits. This is a purely a taxation matter.

Both WTO and OECD matters are coming to an inflection point with vigorous debates/discussions/activities. It would be interesting times for trade and tax policymakers while a new legal paradise gets created for lawyers.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated. Your comment will be online shortly. Kindly excuse the lag