Global Value Chains and India: Policy perspectives and challenges

(This post originally appeared in the World Trade Centre Bangalore newsletter)

The engraving on the back of my phone reads: 'Designed in California; Assembled in China'. It skips the in betweens, as to where the components and sub-assemblies came from. If they indeed decide to do the full list, it might fill the entire back case. On an iPhone, which is designed by Apple in California, the component sourcing will take us through ASEAN, Japan and many other countries. Some of the software and technology that goes into it might again come from US, Germany and other countries. Though the iPhone is finally assembled in China, the value addition by Chinese is less than 10% for each phone shipped out of that country. The value addition is different for other brands of smartphones, depending on sourcing patterns. This is an example of Global Value Chain (GVC) at work, smartphone GVC in this case. GVCs have changed the way one thinks about international trade and related policy making.

Industrial clusters plugs into GVCs. China has shown in last three decades that clustering of similar industries lead to synergies resulting in faster development of the entire sector. The resulting whole is bigger than the sum of its parts. China has spent considerable efforts in developing such clusters by way of SEZs and otherwise. Apart from conscious sectoral push by the Governments, clustering also results when a big firm decides to pitch base at one place, bringing all its suppliers and vendors along to tent nearby. Imagine a Toyota coming into the outskirts of Bangalore and getting most of its primary vendors into Bangalore and nearby areas. Or in coming future, one might imagine a Foxconn trying to set up manufacturing base in India, bringing along its main suppliers. Clustering might also happen spontaneously, like in Silicon Valley, where precipitating conditions required for such development exist. Industrial clustering as a policy tool needs careful thinking again. Our SEZ policy shows how this shouldn’t be done.

Containerisation and globalisation has hastened the process of evolution of GVCs in the last two decades. GVCs have contributed significantly to the development of ASEAN region and China. Countries that integrate themselves to the GVCs get upgraded in terms of technology, as they have to comply with the best international practices in production and quality maintenance. When GVCs encompass industrial clusters, which usually happens for products in late growth and mature stages of product lifecycle, it leads to economies of scale which cannot be easily replicated. The mass manufactured electronic components coming out of such arrangements get sold at price points that wipes out competition relying on alternative strategies. The clustering also leads to faster adoption of process innovations and best practices as the human resource, which is mobile between clustered firms, acts as idea pollinator.

In short, there is no disputing the importance of GVCs and industrial clusters specialising in sectors of manufacturing in the globalised economy. An unplugged country stands to lose heavily and risks being left behind. There are hardly any products, except commodities and low value added agriculture products, that are not produced in value chains spread across countries. From aeroplanes and mobiles to the clothes and shoes we wear and the pills we pop, almost everything comes out of such value chains.

An analysis of India’s Foreign Value Added share in Gross exports over years shows that India is being drawn, willy-nilly, into integrating into the these value chains. This development was also acknowledged in the latest Economic Survey.

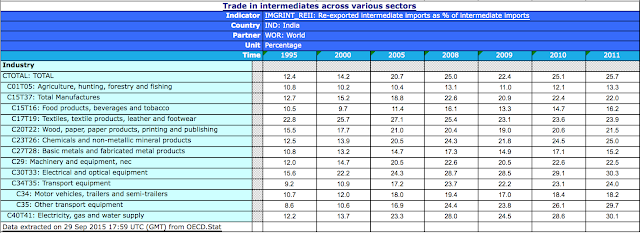

A sectoral analysis of trade in intermediates show that the GVC integration spreads across sectors, except agriculture, mining and metals, where the trade in intermediates is not as significant as in some other sectors. Services integration, appears low at present based on this approach of data collection, is going to grow with time as better policy arrangements are put in place internationally through region trade agreements and multilateral arrangements. The trend in services integration is positive for India.

The data points that we are ‘almost’ there when it comes to integrating with the GVCs of the world. However, it also reveals the challenges. Most of our achievements came during easy times, before 2009, and the progress thereafter has been lacklustre.

Today, we are in a tricky situation. For the past few decades, upto the financial crisis, international trade grew at a rate of around 7% a year, which was almost double the rate of growth of world GDP. Post financial crisis, the trade growth has remained sluggish, and for the last couple of years it has grown at around 3 percent, lesser than the pace of world GDP growth. In terms of trade to GDP share too, the world trade rose from around 40% of world GDP in the early 90s to peak at around 61% in 2011. It has now fallen to around 60%. A rise in 1 percent in global income would have lead to around 2.2 percent of increase in world trade in the 90s, but it lead to a growth of just 1.3 percent in the 2000s. This has fallen further after the financial crisis. This had lead to the theory that the world trade has ‘peaked’.

While economists like Paul Krugman deny the peaking theory, there is a significant risk arising out of slowing trade. One of the theories advanced by IMF (http://goo.gl/IXxy3C) regarding underlying causes for the above pertain to saturation of Global Value Chains. There is good evidence that the phenomenon of fragmentation of manufacturing process that enabled development of GVCs has matured during early 2000s. Further discretisation of manufacturing stages might not happen at the earlier pace.

This would mean that we might be entering a stage where we will have countries trying to capture more share of different GVCs, across sectors, at the cost of others. Also, countries would try to move up the value chain by trying to capture more stages to themselves. To cite an example, Chinese imports of intermediates has fallen from 60% to 35% in last 15 years. The commensurate increase seen in domestic value added percentage in China’s exports vindicates the theory. We also see indigenous Chinese smartphone manufacturers such as Xiaomi sprouting up who operate at the top of the pecking order in the value chain.

This development puts industries involved in GVCs from India in a peculiar position. Given the fact that the exports from India has stayed stagnant for last few years, the issue is serious not only for the industry or firms, but also for the economy. The solution lies in some innovative and radical departure from earlier way of thinking for both industries and policymakers.

Industries participating in GVCs face challenges that are different from purely domestic firms that cater to local market. A tariff wall that helps a purely domestic firm from competition abroad, might act as a barrier for a firm trying to participate in GVC. Also, a small duty at the border might amplify adversely if the good shuttles multiple times at different stages of production. Therefore, the line of thinking that we need to protect our industries by erecting tariff barriers is dangerous for sectors in which there is potential to participate in GVCs. While I don’t suggest that we jump to near zero tariffs from tomorrow, a careful cost-benefit analysis is needed and undue fears of killing domestic industries need to assessed realistically. The negative approach taken by India at the recently concluded ITA-II agreement at WTO, where we declined to agree for tariff reductions in electronic hardware items, needs a serious rethink.

At the second stage, India needs to engage in developing cohesive regulatory regime, with uniform technical and quality standards built into its regional trade agreements. We should focus on developing and engaging in regional value chains that complement GVCs. While a lot of discussion happens on tariff lines and relative comparative advantages, the points on not so easily quantifiable non-tariff barriers get a short change. A poorly drafted quality standard, which acts as a technical barrier and adds to the costs at the border, might throw a domestic firm out of the GVC. A poor IP law would keep high technology products away from the country for the fear of getting copied.

Thirdly, any initiative that eases transaction time and cost at the border, and within, would provide significant advantage. The firms in the GVCs need to maintain just-in-time delivery schedules and border harassment, whether by customs or myriad inspection and licensing agencies, is suicidal. While infrastructure improvements such as power, roads and ports is a medium to long term issue, one can start focusing on cutting down on documentation and trade facilitation at the border as an immediate measure. India’s stand to go ahead with Trade Facilitation Agreement at WTO is significant if implement in true spirit.

The recent initiative of make-in-India, when dovetailed with National Investment and Manufacturing Zones, can lead to significant clustering effect. This needs good investment climate to succeed, and the Govt. appears to be making serious efforts in this regard.

Similarly, Skill India might play an important role too. The trained human resource is a pre-requisite for moving up the value chains or to capture more parts of it. Demographic dividend and the energy of young population of India needs to be harvested through such measures. Availability of trained human resource is a factor that cannot be easily replicated or transferred across borders.

Finally, any amount of unilateral policy efforts by the Government would not suffice if industry plays sleeping partner. Being the primary stakeholders in a punishing market economy, industries need to work with the Government, by providing timely inputs regarding developments in the sector and by covering emerging issues. While the policy might act with a lag, or the policymakers might be oblivious to the latest, the industry cannot afford to nap on developments.

To sum up, while it might be a fact that GVCs have matured and trade might have peaked or saddling, there still is ample scope for moving up the product value chains and to capture more bits of it by careful strategising. A significant country like India, apart from depending on domestic consumption demand, should also focus on this aspect. While it might not be an export led growth story all over again, it might be a case study on value chain domination through better policymaking. A side effect would of course be better export performance.

Comments

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated. Your comment will be online shortly. Kindly excuse the lag